Ladies’ Petition 1866

In 1866, thirteen Ipswich women were among well over a thousand signatories of the ‘Ladies’ Petition’, the first presented to Parliament requesting votes for all female householders. At this time, no women at all could vote in a national or local election, or be elected to Parliament Only men who owned a household worth at least £10 could do so – a tiny percentage of British people.

In Ipswich, most of the signatories lived in or around a small, prosperous area near Christchurch Park. These women were not asking for all adults to be enfranchised – just for women to be allowed to vote on the same terms as men. They were women – some married, some single and some widowed – who would hope to be enfranchised as either they or their husbands met the £10 property qualification.

There was no formal suffrage group in Ipswich to organise getting the Ladies’ Petition signed. It had to be done in just two weeks with news travelling by word of mouth via like-minded friends and neighbours – hence the clustering of petitioners in just a few streets.

Although seventy-three MPs voted in favour of the Petition when it came before Parliament, it was nevertheless roundly defeated. Disappointed by defeat but, at the same time, heartened by the support they had received, women in some major cities such as London and Manchester started their own local suffrage societies.

Harriet Grimwade – Ipswich’s first publicly elected woman

A breakthrough was made in 1869, some three years after the petition, when Parliament passed the Municipal Franchise Act. This extended the vote to women rate-payers in some local elections and enabled them to stand as Poor Law Guardians and, soon afterwards, for membership of School Boards. In Ipswich, when fifty candidates put themselves forward in 1871 for the eleven seats on the inaugural School Board, these included Harriet Isham Grimwade, the only woman.

Harriet Isham Grimwade (1843 -1893) was a powerhouse of philanthropy. Her family, who lived in Norton House, Henley Road, were Liberals and Congregationalists. She founded and ran a girls’ orphanage (Hope House) and the Tanners’ Street Mission, and was active in several local temperance associations.

The other candidates were predominantly local businessmen. Along with the other ‘unsuccessful’ candidates, Miss Grimwade was persuaded to withdraw from the election, until only the required eleven remained to take up their seats unopposed.

However, she succeed in 1880. She topped the School Board poll by over 600 votes to became the town’s first publicly elected woman. Her candidacy was supported by the East Anglian newspaper, which thought she would give a rather staid Board a much needed fillip.

Miss Grimwade served on Ipswich School Board for six years. She was co-opted onto several of its committees immediately, including School Management and Needlework.

Ipswich and County Women’s Suffrage Society / Ipswich Committee

In 1871, five years after the Ladies’ Petition, Millicent Garrett Fawcett came to speak in Ipswich. She was a nationally known campaigner, one of the famous Garrett clan from Aldeburgh. Accompanied by her father, Newson Garrett, and cousin, Rhoda, Mrs Garrett Fawcett urged a packed audience at Ipswich Lecture Hall to set up a local votes-for-women group. A few months letter, the local press carried the news that Ipswich’s first women’s suffrage organisation had just been established. It was called the Ipswich and County Women’s Suffrage Society although its exact formal name seems to have changed slightly over the years. Usually it was just known as the Ipswich Committee. Its first secretary was the very same Harriet Grimwade who would later serve on the School Board.

It was slow going, though. In Ipswich, as elsewhere, campaigners organised numerous public meetings, petitions, and letters to politicians. They distributed free literature, demanding the vote on the same terms “as it is, or may be” granted to men.

A major disappointment came in 1884 with the passing of a Reform Bill which meant that, in Suffolk for example, three-quarters of county’s agricultural labourers were enfranchised but women were again excluded.

In 1897, Millicent Garrett Fawcett brought several suffrage societies together to work as the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). It seems that the Ipswich Committee never formally joined the NUWSS but were definitely fellow-travellers.

‘Deeds not words’ – WSPU

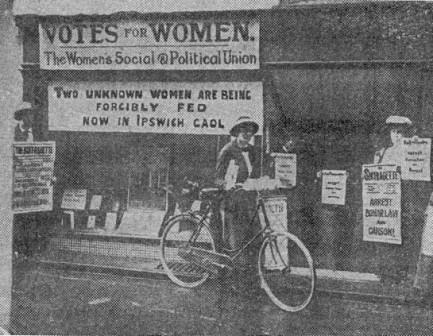

Frustrated with the NUWSS’s lack of success, a new organisation, the Women’s Social Political Union (WSPU), was founded in Manchester in 1903 by six women, including Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst . They were to take direct militant action to make suffrage an active issue, their watch-words being’deeds not words’.

The first WSPU Organiser arrived in Ipswich in 1910. She was Miss Grace Roe, a young and enthusiastic Anglo-Irish suffragette of independent means. Her office was in Silent Street. She opened a fund-raising shop and decorated the window with banners in green, white and purple – the WSPU colours. Reports in the Votes for Women newspaper show her organising public meetings in the town with nationally-known WSPU speakers, setting up drawing room meetings, and appealing for volunteers to sell newspapers and staff the shop.

Miss Andrews and the Women’s Freedom League

Not all suffragists supported the WSPU’s violent tactics or felt comfortable with the way the organisation was dominated by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. By the same token, some these women wanted do more than just attend meetings and write letters. One such Ipswich activist was Constance Andrews. She did not support violence but, equally, felt that softly-softly approaches were ineffective. She wanted to ‘rouse the women of Ipswich’. So she left the Ipswich Committee and joined the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), setting up what was to become a very active Ipswich branch. The WFL was a splinter group from the WSPU and promoted non-violent militant action. Under Miss Andrew’s leadership, the Ipswich group staged pageants and exhibitions, took part in marches and demonstrations in London, and ran three distinctive and high profile local campaigns:

No vote, no tax

Why should a woman pay tax when she did not have the right to vote? This was the basis of the WFL tax resistance campaign. The first local to resist was Mrs Hortense Lane in 1909. Two years later, Constance Andrews, herself, joined the campaign. She refused to get a licence for her pet dog as an act of civil disobedience, refused to pay the fine and, as a result, she was sentenced to one week in Ipswich Prison. The following week she was released amidst a blaze of publicity, telling supporters that every woman should withhold the dog tax – and if they did not have a dog, then they should go out and buy one!

Caravan mission

The WFL in Ipswich raised funds to buy a caravan to take the female suffrage message out to the villages. It first left Ipswich in 1909 and headed off for the village of Debenham:

‘all along the route women waved us encouragement, and on our arrival people took a great deal of trouble finding us a pitch. We are settled in a field by a stream and have invited village women to come and talk this afternoon.’ (Dr Elizabeth Knight)

Caravan and Motorhome Club Magazine, July 2018

Despite this warm welcome, there were occasional hostile crowds and bad weather, but the following year it set off again to continue its work, this time in Felixstowe.

Census boycott

In April 1911, about thirty votes-for-women campaigners spent the night in the Old Museum Rooms (now Arlington’s in Museum Street) to avoid filling in their national census returns. They maintained that if they were considered intelligent enough to fill in a census form, then they could surely put an X on a ballot paper. The stalwarts, including Constance Andrews and her sister had supper together, sang protest songs, played cards and talked about the movement through the night. Police kept a watch to maintain law and order.

In January 1912, Miss Andrews left Ipswich for London to work for the WFL at a national level. She handed over the local reins to her sister and then to Marie Hossack who had also been active in the campaign for several years. Later, one of Mrs Hossack’s housemaids remembered:

‘I was in service in Berners Street with Mrs Hossack, the doctor’s wife. She was a suffragette. I don’t know what they did in Ipswich but she told me she used to go to London and tie herself to the railings down there. She was one of the chief ones in Ipswich.’ (Mrs Harvey)

As a trade unionist and socialist, Constance Andrews wanted to try to engage working class women in the campaign for votes, believing that women needed more than the ‘bricks and mortar’ suffrage demanded by some other campaigners. To date, direct evidence suggests that the Ipswich suffragists were overwhelmingly middle-class women but it is highly likely that some of their working class sisters were involved. For example, in 1910, Miss Andrews helped set up a branch of the National Federation of Women Workers for Ipswich corset workers. They must certainly have discussed this burning issue of the day at branch meetings.

End of militancy

In 1914, in what would prove to be a last audacious act in Suffolk, two votes for women campaigners set fire to the Bath Hotel in Felixstowe. They were thought to be WSPU members lodging at 19 Berners Street. Held on remand in Ipswich Prison, they were said to be on hunger strike and being forcibly fed. The affair became a talking point in the 1914 by-election which was held in Ipswich just before war with Germany was declared.

(Women’s Library at LSE)

In the summer of 1914, all suffragettes were released from prison now that Britain was at war. Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst decided that the fight for suffrage should wait until peacetime and the WSPU branch in Ipswich, as in many other towns, was disbanded. The militant campaign had come to an end. The WFL and the NUWSS retained their organisations, however, and are listed in the 1916 Suffolk County Handbook. Their local leaders were by now stalwarts of many years standing.

Partial victory (1918)

A partial victory for suffrage campaigners came in February 1918 when the Representation of the People Act, passed in early 1918, gave the vote to all men over 21 and to women over 30 who were occupiers of property (or married to occupiers). The first Westminster election after this legislation was held in December 1918 and Jack Ganzoni, the sitting ‘soldier’ MP was returned. For this election, according to The Times, just over 40% of eligible voters in Ipswich were women (16,000 were listed on the Ipswich electoral register out of a total of 37,000).

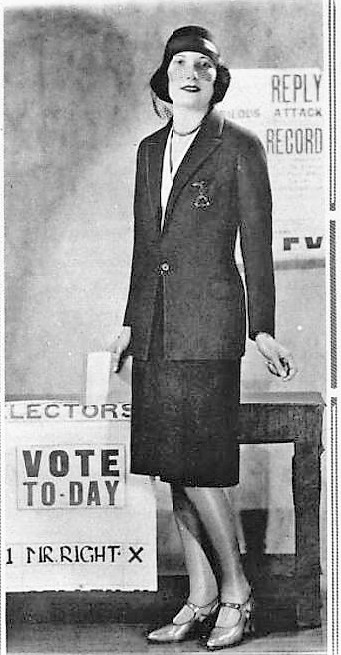

The ‘Flapper’ Election (1929)

The Equal Franchise Act was passed in 1928 and, in the following year, the first election was held in which men and women had the same voting rights as each other. In Ipswich, the 1929 electoral register contained nearly twelve thousand more names than the year before. Many of these would have been working-class women who had become qualified to vote for the first time.

(The Sketch, 1929)

The Conservative Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, came to Ipswich electioneering in 1929 and addressed over 2000 voters at the Hippodrome. Lady Blanche Cobbold was there to represent newly qualified electors, who, unlike herself, were mostly working class women. And the sitting Tory MP, Jack Ganzoni, joked about how he had wooed the ladies:

‘I’ve done my best. … as far as possible I’ve kissed every pretty girl in Ipswich.’ (Nottingham Post, 22 May 1929)

Despite this wearisome piece of banter, Ganzoni kept his seat but his majority was reduced. Nationally, there was a hung parliament with fourteen women MPs. To date, Ipswich has not yet elected a woman to represent the town in Parliament.

Sources include

- Song of their Own by Joy Bounds (History Press, 2014)

- British Newspaper Archive (online)

- Local conditions for the experience and activities of women: the case of Ipswich 1875 – 1900, J. Collier 1993, MA Social History. (942.649 at SRO)

- The National Federation of Women Workers by Cathy Hunt (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)